Hi! Here's the material you'll need for Lebanon Valley College's course Dead or Ecstatic, a Survey of English Literature I: the Middle Ages to 1800 (ENG 225.02):

Vivian Darkbloom in Pretty Little Liars

"Very few people know Vivian's true identity," says the Pretty Little Liars wiki.

Vladimir Nabokov's anagram, Vivian Darkbloom, has appeared in Ada and Lolita (and in the Acknowledgments page of Arthur Philips's The Egyptologist). She now also appears in the ABC Family series Pretty Little Liars, where Vivian is the alter-ego of Alison DiLaurentis.

Thanks to the Nabokv-L Listserv and to Jansy Mello for the tip.

Vladimir Nabokov's anagram, Vivian Darkbloom, has appeared in Ada and Lolita (and in the Acknowledgments page of Arthur Philips's The Egyptologist). She now also appears in the ABC Family series Pretty Little Liars, where Vivian is the alter-ego of Alison DiLaurentis.

Thanks to the Nabokv-L Listserv and to Jansy Mello for the tip.

Montaigne and the Tauntaun

Montaigne on the historical precedent for the apparently-scientifically-improbable Star Wars bit where Han Solo stuffs Luke Skywalker into the Tauntaun: The army that Bajazet had sent into Russia was overwhelmed with so dreadful a tempest of snow, that to shelter and preserve themselves from the cold, many killed and embowelled their horses, to creep into their bellies and enjoy the benefit of that vital heat. (From On War Horses in The Complete Essays.)

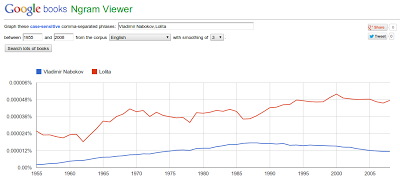

"Lolita is Famous, Not I," Visualized

In Strong Opinions, Nabokov claims that "Lolita is famous, not I. I am an obscure, doubly obscure, novelist with an unpronounceable name." This Google Ngram Viewer graph appears to prove him right.

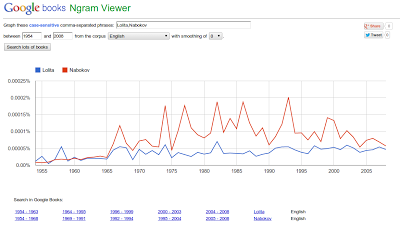

But: If you remove "Vladimir" (making his name maybe 50% less unpronounceable) and remove the smoothing, the Ngram Viewer graph tells a different story: "Lolita" triumphs over Nabokov only in 1955 and 1958, the dates of Lolita's France and American publications. (Big ups to Chris Manon for pointing this out.)

But: If you remove "Vladimir" (making his name maybe 50% less unpronounceable) and remove the smoothing, the Ngram Viewer graph tells a different story: "Lolita" triumphs over Nabokov only in 1955 and 1958, the dates of Lolita's France and American publications. (Big ups to Chris Manon for pointing this out.)

Craigslist, Montaigne-style

Montaigne's dad points out the need for Craigslist several centuries before it finally came around:

My late father, a man that had no other advantages than experience and his own natural parts, was nevertheless of a very clear judgment, formerly told me that he once had thoughts of endeavouring to introduce this practice; that there might be in every city a certain place assigned to which such as stood in need of anything might repair, and have their business entered by an officer appointed for that purpose. As for example: I want a chapman to buy my pearls; I want one that has pearls to sell; such a one wants company to go to Paris; such a one seeks a servant of such a quality; such a one a master; such a one such an artificer; some inquiring for one thing, some for another, every one according to what he wants. And doubtless, these mutual advertisements would be of no contemptible advantage to the public correspondence and intelligence: for there are evermore conditions that hunt after one another, and for want of knowing one another's occasions leave men in very great necessity.

From ~1592's Of One Defect in Our Government, in the Complete Essays.

Nabokovilia: Updike's The Afterlife and Other Stories

From Updike's The Afterlife and Other Stories:

"Don't make me laugh. I'll get urinary impotence." It was a concept of Nabokov's, out of Pale Fire, that they both had admired, in the days when their courtship had tentatively proceeded through the socially acceptable sharing of books. She managed. In Ireland's great silence of abandonment the tender splashing sound seemed loud. Psshshshblippip. Allenson looked up to see if the hawks were watching. Hawks could read a newspaper, he hand once read, from the height of a mile. But what could they make of it?

"Don't make me laugh. I'll get urinary impotence." It was a concept of Nabokov's, out of Pale Fire, that they both had admired, in the days when their courtship had tentatively proceeded through the socially acceptable sharing of books. She managed. In Ireland's great silence of abandonment the tender splashing sound seemed loud. Psshshshblippip. Allenson looked up to see if the hawks were watching. Hawks could read a newspaper, he hand once read, from the height of a mile. But what could they make of it?

Two Pieces in TriQuarterly

Also: Selected Shorts rebroadcast "Customer Service at the Karaoke Don Quixote this month"! Parker Posey guest-hosted! (MP3 available here.)

SIGHTING: Nabokov Wins One for the Islanders

Andrea Pitzer, author of The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov, wrote an exceedingly funny McSweeney's bit where she replaces the eponymous hockey-player with the writer: Nabokov Wins One for the Islanders.

(This is not, incidentally, the first time Nabokov appears in McSweeney's. See also Nabokov Didn't Have to Put Up with Payroll and Less is Best, Mr. Nabokov.)

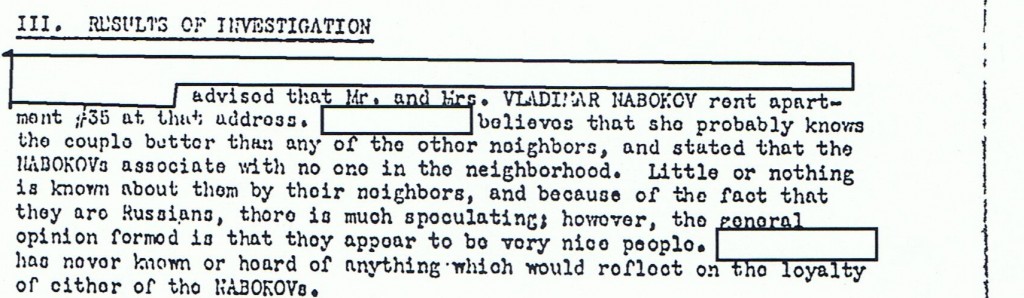

VN SIGHTING: "They appear to be very nice people."

From the blog associated with Andrea Pitzer's awesome The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov, excerpts from an FBI report on Vera and Vladimir newly arrived in the States. The takeaway? "The NABOKOVs associate with no one in the neighborhood," but "they appear to be very nice people." Very nice people indeed! And happy belated birthday, VN!

Sightings: Nabokov at Cornell and Harvard

|

| Isaiah Berlin |

Nabokov is asked for translation help from a lovestruck Isaiah Berlin. Frances Assa summarizes what happens next:

I’ve been reading Michael Igniatieff’s biography of Isaiah Berlin. At this time (1949) Berlin was a pleasant but sexless Oxford don who suddenly, at age forty, fell violently in love. While teaching at Harvard that year, he was translating Turgenev’s First Love into English and unsure of how to translate the hero’s sudden rush of feeling when the beloved responds to his interest. Ignatieff tells us that Berlin was asking friends if it was correct to say “that your heart ‘turned over’ when your loving glance was first returned? Or should he say that the heart ‘slipped its moorings’?” and totally misses the comedy when he reports what happened when Berlin asked Nabokov for help:

"While at Harvard, Isaiah actually consulted Vladimir Nabokov—then a research fellow in Lepidoptera at the Harvard zoology department—on how to translate this particular passage. Nabokov’s suggestion—‘my heart went pit a pat’—left Isaiah unimpressed. Finally, he settled on ‘my heart leaped within me’."Nabokov quizzes a student, the student flails and provides a wildly erroneous answer, and the following ensues:

Only after the exam did I learn that many of the details I described from the movie were not in the book. Evidently, the director Julien Duvivier had had ideas of his own. Consequently, when Nabokov asked “seat 121” to report to his office after class, I fully expected to be failed, or even thrown out of Dirty Lit.

What I had not taken into account was Nabokov’s theory that great novelists create pictures in the minds of their readers that go far beyond what they describe in the words in their books. In any case, since I was presumably the only one taking the exam to confirm his theory by describing what was not in the book, and since he apparently had no idea of Duvivier’s film, he not only gave me the numerical equivalent of an A, but offered me a one-day-a-week job as an “auxiliary course assistant.” I was to be paid $10 a week.

The full story for the above quote comes from Edward Jay Epstein's An A From Nabokov in the New York Review of Books. The first quote comes from Frances Assa's post to the Nabokv-L Listserv.

Sighting: Mantel and Pnin

From Ian Crouch's Hilary Mantel and the Pitfalls of the Public Lecture:

She might have suffered the transportation indignities of Nabokov’s poor Professor Timofey Pnin, who, when we meet him, is seated comfortably in a compartment on what we learn is the wrong train, on his way to deliver a lecture—“Are the Russian People Communist?”—to the august ladies of the Cremona Women’s Club. He soon learns of the mistake, too, and a conductor sends him from the train to wait for a promised bus. What follows qualifies, as the narrator promises, as “still better sessions in the way of humor.”

She might have suffered the transportation indignities of Nabokov’s poor Professor Timofey Pnin, who, when we meet him, is seated comfortably in a compartment on what we learn is the wrong train, on his way to deliver a lecture—“Are the Russian People Communist?”—to the august ladies of the Cremona Women’s Club. He soon learns of the mistake, too, and a conductor sends him from the train to wait for a promised bus. What follows qualifies, as the narrator promises, as “still better sessions in the way of humor.”

Sighting: David Foster Wallace's Roll Call

Adam Plunkett's N+1 memoir and appreciation of David Foster Wallace as a teacher features this Nabokov-minded bit:

It took a student a few seconds to answer when called on “Joseph Reynolds, light of my life, fire of my loins” (name changed to protect privacy). My own soft underbelly was spoken (if not written) politeness, a Midwestern habit of deference and sorrys and if-you-don’t-minds my Midwestern teacher invariably mentioned or mocked or prodded in a mild recursive torment, recursive because politeness tends to be polite about itself.

It took a student a few seconds to answer when called on “Joseph Reynolds, light of my life, fire of my loins” (name changed to protect privacy). My own soft underbelly was spoken (if not written) politeness, a Midwestern habit of deference and sorrys and if-you-don’t-minds my Midwestern teacher invariably mentioned or mocked or prodded in a mild recursive torment, recursive because politeness tends to be polite about itself.

I Read!

Nabokovilia: Michael Chabon

The Yiddish Policemen’s Union (2007)

Afterword: ...the Zugzwang of Mendel Shpilman was devised by Reb Vladimir Nabokov and is presented in Speak, Memory. (p. 418)

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (2000)

Here, in a weird radiance cast by the tails of a thousand writhing glowworms, sits on a barbarous throne a raven-haired giantess with immense green wings, sensuously furred antennae, and a sharp expression. She is, quite obviously, the Cimmerian moth goddess, Lo. We know it before she even opens her rowanberry mouth.

"You?" the goddess says, her feelers wilting in evident dismay. "You are the one the book has chosen? You are to be the next Mistress of the Night?"

Miss [Judy] Dark -- wreathed discreetly now in curling tufts of dry-ice smoke -- concedes that it seems unlikely. (p. 271)

Wonder Boys (1995)

"You have to keep with it," I told him. "You have to read on." I was making the argument I had made to myself, over the years -- to the harsh and unremitting editor who lived in the deepest recesses of my gut. It sounded awfully thin, spoken aloud at last. "It's that kind of a book. Like Ada, you know, or Gravity's Rainbow. It teaches you how to read it as you go along. Or -- Kravnik's." (p. 312)

Additional Chabon/Nabokov material:

"You have to keep with it," I told him. "You have to read on." I was making the argument I had made to myself, over the years -- to the harsh and unremitting editor who lived in the deepest recesses of my gut. It sounded awfully thin, spoken aloud at last. "It's that kind of a book. Like Ada, you know, or Gravity's Rainbow. It teaches you how to read it as you go along. Or -- Kravnik's." (p. 312)

Additional Chabon/Nabokov material:

- Michael Chabon at the Nabokov Museum (also collected in Maps and Legends)

- Michael Chabon on Wes Anderson

VN Sighting: Michael Chabon on Wes Anderson's Nabokovian Worlds

In this lovely essay for the New York Review of Books, Michael Chabon notes the parallel scale-world-building impulses of Vladimir Nabokov and Wes Anderson:

Vladimir Nabokov, his life cleaved by exile, created a miniature version of the homeland he would never see again and tucked it, with a jeweler’s precision, into the housing of John Shade’s miniature epic of family sorrow. Anderson—who has suggested that the breakup of his parents’ marriage was a defining experience of his life—adopts a Nabokovian procedure with the families or quasi families at the heart of all his films, from Rushmore forward, creating a series of scale-model households that, like the Zemblas and Estotilands and other lost “kingdoms by the sea” in Nabokov, intensify our experience of brokenness and loss by compressing them. That is the paradoxical power of the scale model; a child holding a globe has a more direct, more intuitive grasp of the earth’s scope and variety, of its local vastness and its cosmic tininess, than a man who spends a year in circumnavigation.Chabon himself is no stranger to world-building, or to Nabokovilia: he has made Nabokov references in Wonder Boys, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, and in The Yiddish Policemen's Union.

Sebald on Writing

Check out Max Sebald's Writing Tips!

I've been collecting some of my favorite writers' advice on writing, and it's a treat to add W.G. Sebald to the list -- all thanks to two students in that final semester in East Anglia who wrote down some of what Sebald said in class. There are no recordings of him teaching, apparently, and so the record is scant but awesome.

All of the advice is sensible, and useful to anyone, but the more of these I read, the more it feels like this is advice tailored specifically to the writer giving it, which makes total sense: "Fiction," Sebald says, "should have a ghostlike presence in it somewhere, something omniscient. It makes it a different reality." Which helps everyone out, but it is most helpful if the writer getting the advice is writing The Emigrants. Or The Rings of Saturn.

We tend to accidentally reflect our current preoccupations, our bent and disposition, when we are asked for advice: to turn the general and universal into the particular and the individual. I don't know if there's any helping it, nor do I think it's a bad thing -- the best advice comes from whatever you've wrestled yourself. But it does remind me that I used to proofread in Orlando for this outfit that put together the entertainment pages of regional and Metro newspapers, so I read hundreds of bridge columns, and also an untold number of astrology columns. And I was most struck that -- read sequentially, as I had to -- an astrology column reflects not so much the reader's state but the writer's. What his or her current nagging thought is. ("LIBRA: Today is a good day for shopping! SCORPIO: Maybe you should think about your savings. PISCES: Seize the day! Have fun!")

Not a bad thing, though. And a sensible way to go about the world: be generous with what you've learned, and be aware that what you've learned comes from stuff that's way particular to your own experience. What you carry with you shapes how you see the world, and how you go about the world. Which reminds me of the weird congruence between the discovery of the rubber heel and a famous passage from Santideva's Way of the Bodhisattva.

On the discovery of the rubber heel:

I've been collecting some of my favorite writers' advice on writing, and it's a treat to add W.G. Sebald to the list -- all thanks to two students in that final semester in East Anglia who wrote down some of what Sebald said in class. There are no recordings of him teaching, apparently, and so the record is scant but awesome.

All of the advice is sensible, and useful to anyone, but the more of these I read, the more it feels like this is advice tailored specifically to the writer giving it, which makes total sense: "Fiction," Sebald says, "should have a ghostlike presence in it somewhere, something omniscient. It makes it a different reality." Which helps everyone out, but it is most helpful if the writer getting the advice is writing The Emigrants. Or The Rings of Saturn.

We tend to accidentally reflect our current preoccupations, our bent and disposition, when we are asked for advice: to turn the general and universal into the particular and the individual. I don't know if there's any helping it, nor do I think it's a bad thing -- the best advice comes from whatever you've wrestled yourself. But it does remind me that I used to proofread in Orlando for this outfit that put together the entertainment pages of regional and Metro newspapers, so I read hundreds of bridge columns, and also an untold number of astrology columns. And I was most struck that -- read sequentially, as I had to -- an astrology column reflects not so much the reader's state but the writer's. What his or her current nagging thought is. ("LIBRA: Today is a good day for shopping! SCORPIO: Maybe you should think about your savings. PISCES: Seize the day! Have fun!")

Not a bad thing, though. And a sensible way to go about the world: be generous with what you've learned, and be aware that what you've learned comes from stuff that's way particular to your own experience. What you carry with you shapes how you see the world, and how you go about the world. Which reminds me of the weird congruence between the discovery of the rubber heel and a famous passage from Santideva's Way of the Bodhisattva.

On the discovery of the rubber heel:

The story goes, as documented in a typewritten page dated 1926 (source unknown), in 1896 Humphrey O'Sullivan was a young printer in Lowell, Massachusetts. He walked on a stone floor while feeding a printing press, and to ease his footsteps, he bought a rubber mat on which to stand. His fellow employees kept "borrowing" the mat, so Humphrey cut out two pieces of the mat the size of his heels and nailed them to his shoes. The results pleased and astonished him.On how training one's mind is like wearing shoes:

Where would I find enough leatherOn quoting:

To cover the entire surface of the earth?

But with leather soles beneath my feet,

It’s as if the whole world has been covered

Don’t be afraid to bring in strange, eloquent quotations and graft them into your story. It enriches the prose. Quotations are like yeast or some ingredient one adds.

That last one is Sebald's. Good morning!

Bring Up Half the Bodies: Creative Writing Workshop: Fiction (ENG 219.01)

Hi! Here's the material you'll need for Lebanon Valley College's course Bring Up Half the Bodies: Creative Writing Workshop:Fiction (ENG 219.01), taught by professor Juan Martinez:

- Course syllabus

- Story guidelines

- Peer Feedback guidelines

- Final portfolio guidelines

- First set of story constraints for story due 7 February 2013

- Second set of story constraints for story due 14 March 2013

- Third set of story constraints for story due 11 April 2013

- Our calendar of due dates, exams, and readings

Remember that you can always contact your professor at martinez@lvc.edu. You can also leave comments below (or on the individual pages linked above) and I'll be happy to answer them there as well.

English Communications II: ENG 112 07 & 12

Hi! Here's the material you'll need for Lebanon Valley College's English Communications 2 course, sections 07 & 12 (ENG112.07 & ENG112.12):

- Course syllabus

- Project One guidelines

- Project Two guidelines

- Project Three guidelines

- Project Four guidelines

- Our calendar of conferences, due dates, and readings

Our Readings

- For Poor, Leap to College Often Ends in Hard Fall

- Here is What Happens When You Cast Lindsay Lohan in a Movie

- The Apology of Plato, by Socrates

- My Apology, by Woody Allen

- A selection of This I Believe essays

- David Foster Wallace's This is Water.

Remember that you can always contact your professor at martinez@lvc.edu. You can also leave comments below (or on the individual pages linked above) and I'll be happy to answer them there as well.

Sighting: Nabokov Tweets!

Nabokov! On Twitter! See what he's saying. Brilliant idea, and hats off to whoever came up with it.

Great Beginnings!

So the Selected Shorts episode with my story "Best Worst American" in it aired this weekend! It's here (the 10/21 episode titled "Great Beginnings").

And here's the full interview of Keret and Tinti talking about the stories in the episode, mine included.).

You can get to the actual MP3 of the episode here, where Cristin Milioti does an awesome job reading the piece.

And here's the full interview of Keret and Tinti talking about the stories in the episode, mine included.).

You can get to the actual MP3 of the episode here, where Cristin Milioti does an awesome job reading the piece.